In 589 the period of Northern and Southern Dynasties ended when China was finally unified under the Sui Dynasty. Much like the earlier Qin Dynasty the Sui consolidated the country and set the foundation for the next dynasty to last centuries. The most important Sui achievement was to create the Grand Canal to connect the Yellow River in the North with the Yangtze in the South. The importance of the Grand Canal to China’s long-term economic prosperity is difficult to overstate. Throughout the pre-modern world, water routes were the most efficient way to move any good in quantity- such as grain or rice. The Grand Canal enabled trade within China to transcend trade in luxuries and led to urbanization and commercialization alongside the route of the Grand Canal. Although the long-term benefits were immense in the short-term coerced peasants resented the process. The Sui also set to rebuild the Qin Great Wall to protect them from nomadic incursions. In addition to the work for the benefit of the country, the Sui emperors Wei and Yang also spent immense sums on personal palaces and other luxuries. Yet the straw that broke the dynasties back was the military campaigns of Emperor Yang, most notably three invasions of the Korean kingdom of Koguryŏ. According to Chinese sources, over a million men were drafted for these failed expeditions. At last, in 611 rebellions began against the Sui, and Emperor Yang was assassinated in 618.

The Sui were replaced with the Li family, the dukes of Tang, and thus took the name of the Tang Dynasty. Like many of the elites of Northern China, the Tang were ethnically mixed between the Han and the various ethnic backgrounds of China’s nomadic neighbors. The first Tang ruler Li Yuan reunited the country and paid off the nomadic Turks to prevent their invasion. Li was overthrown by his son, who after killing his brothers declared himself the emperor Taizong. Despite his violent rise- Taizong would be remembered as an ideal Confucian ruler. Taizong stopped payments to the Turks and after a victorious campaign was declared the ruler (Heavenly Qaghan) of the Turks in 630. This would begin several centuries of Tang dominance in Central Asia- providing stability to the routes of the Silk Road.

Emperor Taizong receiving a Tibetan Ambassador.

Taizong was in turn succeeded by his son Gaozong whose reign was dominated by his spouse Wu Zetian. Gaozong implemented the famed Tang law code- which in modification was influential until the 20th century. After Gaozong’s death in 689, Wu reigned as regent for both her sons and later in her own name- the only female ruler in the history of imperial China. Historical sources- written by Confucian scholars are uniformly hostile to her. They portray her as deceitful, violent (including the killing of her child), and sexually deprived while begrudgingly admitting her administrative competence[1]. The truth of these stories is debatable. Wu was particularly notable as a great patron of Buddhism and responsible for patronizing some of the most iconic Buddhist art in the Chinese tradition such as the Longmen Grotto outside of Luoyang. After Wu was overthrown and forced to commit suicide in 710, the Li family was returned to power under Emperor Xaunzong whose reign from 710-to 756 is considered the height of the Tang

The two imperial cities of the Tang Dynasty were Chang-An (today Xi’an) and Luoyang. Chang-An was re-founded by the Sui as a political center but soon grew into an economic and religious terminus at the end of the Silk Road. Political embassies arrived from Heian Japan, the three Korean kingdoms, Central Asian rulers, Indochina, and even from the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic Caliphates. Korean and Japanese elites sent their children to study in the academies of Chang-an. The last Sassanid Persian prince retired in Chang-an after the Islamic conquest. Chang-An was also the center of the Tang central government- which directly employed 11,312 civil servants at one point. Although this is a substantial number much of the energy was focused on the person of the emperor. At one point there were 2779 employees in the Ministry of Imperial Entertainment and only 191 in the Ministry of Justice [2].

The two imperial cities each had a population approaching one million and were the largest cities anywhere in the world at the time. Both cities were laid out in an orderly fashion along with a chessboard pattern. Trade during the early Tang period was heavily regulated and confined to official markets. At night in Chang-an, travel was banned between different wards of the city to preserve order. The Sogdians, a Central Asian people, played a dominant role in trade in the cities- selling goods from the West brought along the Silk Road. The cityscape was dominated by countless temples and monasteries- primarily Taoist and Buddhist. The city itself became a site of Buddhist pilgrimage. Zoroastrian Temples, (founded by the exiled Sassanid Emperor), Manichaean places of worship, Nestorian Christian Churches, and Islamic Mosques could also be found in Chang-an to cater to the spiritual needs of both traders and immigrant communities.

For Tang elites, Chang-An was the center of the world. Even a high-ranking post in the provinces was considered a type of exile. The path to the elite was the imperial exams but during the Tang period, the exams were primarily reserved for the most powerful families. Unlike in later periods of Chinese history when exams were graded anonymously on merit- outright lobbying was encouraged during the Tang. The “character” of one’s family was still considered to be of importance and an aristocracy of a few prominent families dominated government in the early Tang era[3]. The exams themselves were primarily literary - although at some points more practical matters of government were also covered.

In the later Chinese memory, the Tang would be best remembered as the golden age of Chinese poetry. During this period poetry went from being an activity practiced primarily at the imperial court to an activity performed by professionals in cities. The actual meaning and voice of poems became more important than the formal rules. Poets often saw their work as being like that of Buddhist monks- sacrificing all things in life for artistic inspiration rather than enlightenment. This devotion transcended social hierarchy and poets observed a sense of social equality amongst themselves[4]. The poet Zhou Pu went as far as to proclaim in a poem addressed to the Chan Buddhist monk Dawei;

“For Chan it is Dawei, for poetry Zhou Pu,

With the Great Tang’s Son of Heaven, just three people.”[5]

Thus, the monk, the poet, and the emperor each constitute three separate but important roles in society- that are in a sense comparable.

The Tang Emperors were themselves fabulous poets and active patrons of the arts. The emperor Taizong was famously buried with his most prized possession- the calligraphy of the great fourth-century master Wang Xizhi[6]. Emperor Xaunzong (r. 713-756) was one of the most prolific sponsors of the arts in the history of China. In the early part of his reign, he proved to be competent in fiscal and administrative matters and oversaw the height of the Tang. However, by the 740s his focus shifted to artistic and sexual endeavors with his favorite concubine Yang Guifei. Regional governors- especially in the north became increasingly autonomous. A favorite of Yang’s- governor-general An-Lushan of Sogdian and Turkish descent, became especially powerful. Fearing for his position because of a rivalry with one of Yang’s relatives, An-Lushan revolted in 755. Within a month he had captured Luoyang and after a major defeat, Xaunzong fled to Chengdu in Sichuan. En route, his bodyguard mutinied and demanded the execution of Yang Guifei. Soon after his son disposed of him. Over the coming decade, war-ravaged Northern China while the South was mostly spared.

The eventual Tang victory in 763 was the result of compromises by the Tang. The Tang lost real power over most of the North to autonomous governors and in South saw the rise of powerful landlords and officials in charge at a local level. The Tang also forged an alliance with the Uighurs and Sogdians against attacks from the emerging Tibetan kingdom. Tang influence in Central Asia completely ended. Even before the rebellion, the Tibetans and Islamic Caliphate had challenged Chinese preeminence in the region. In 751 the Tang had lost the battle of Talas River to forces of the Abbasid Caliphate. The Abbasids also captured several skilled papermakers helping spread the technology throughout the Islamic world.

The chaos also accelerated the process of China’s population moving south to the Yangtze Valley and below. According to the official census, the population decreased from 52,880,488 in 754 to 16,900,000 in 769[7]. Most of this reflects government weakness in the aftermath of the rebellion rather than deaths from the war[8]. China’s center of gravity shifted to the cities on the Grand Canal such as Jiangdu whose population grew from 40,000 to 500,000 during the Tang period[9]. Overall, from 742 to 1080 the population of the North increased by 26% and the population of the South by 328%[10]. The tax code was simplified in 780 under the two-tax system whereby two taxes were collected- a progressive income tax in cash and a grain tax based on the value of the land. The other primary source of revenue was the state monopolies on salt and iron run by the powerful Salt and Iron Commission- which became the de-facto ruler of much of Southern China during the later Tang. As progressive as this system might sound on paper-it also marked the end of the Chinese state trying to ensure equity among the peasantry or to protect them from becoming tenants of large landlords.

The need to pay some taxes in cash encouraged many peasants to become engaged in growing commercial crops such as tea. Tea especially became a heavily commercialized industry- popular especially with Buddhist monks who were not supposed to eat solid food in the afternoon. Buddhist monasteries were major centers of both charitable and intellectual endeavors. While Buddhism declined in India four unique schools of Chinese Buddhism emerged. Commerce thrived South of the Yangtze and the central government began experimenting with paper money and checking (known as flying money). Foreign trade also shifted as the ancient Silk Road grew more dangerous, Trade routes shifted to the seas and the great port cities of Guangzhou, Hangzhou, and Panyu which had a large population of Arabs, Indians, Malays, and Javanese. By 879 a community of thousands of Muslim Arabs and Persians had settled in Guangzhou[11].

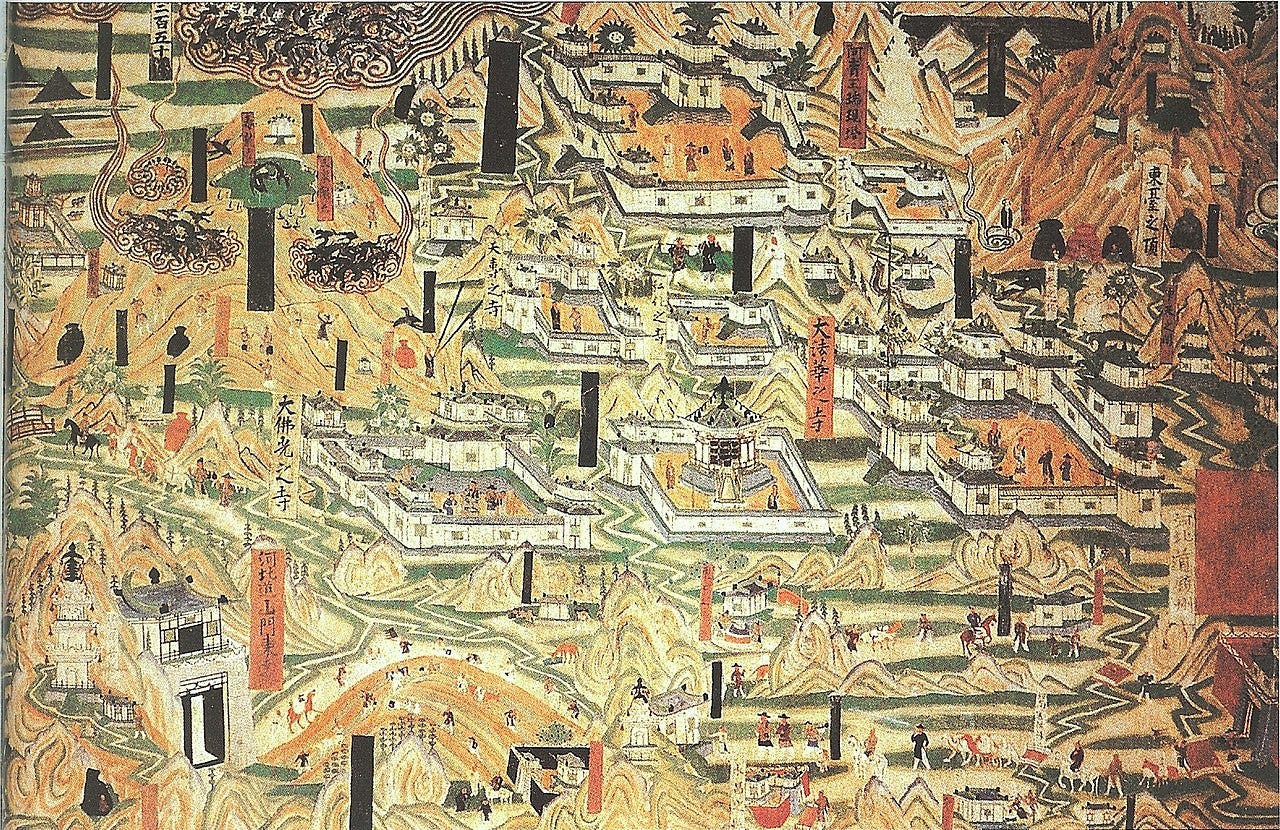

10th-century mural painting in the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang showing the monastic architecture of the Tang.

Despite prosperity and cosmopolitanism in the South, the Tang state continued to weaken, and xenophobia rose across the country. After the reign of the wise reformist Xianzong from 805 to 820, court eunuchs dominated weak and often teenage emperors. Facing a growing fiscal crisis, the emperor Xuanzong ordered the appropriation of 4,600 Buddhist monasteries in 841 and compelled 265,000 tax-exempt monks and nuns to become tax-paying farmers. Millions of Buddhist sculptures were melted for gold or destroyed. Many Confucian scholars supported the persecution, echoing the sentiment of an official in 819 who implored the emperor not to venerate a bone relic of the Buddha because the Buddha was, “a man of the barbarians who did not speak the language of China and wore clothes of a different fashion.”[12] The idea that enlightenment could come from a barbarian man who did not understand the customs of the Middle Kingdom was outrageous to this Confucian scholar. For two years Xuanzong rescinded his anti-Buddhist edicts, but later Tang emperors would continue persecution and plunder when fiscally or politically expedient. As a result, only 2,694 monasteries remained in 960 out of 30,326 that existed before the purge[13].

Bandits, who found willing recruits among increasingly impoverished peasants, arose across the Chinese countryside. The unsuccessful examination candidate Huang Chao became the most successful. In 879 his armies took over the great port city of Guangzhou and ordered a massacre of the city's Arab, Persian, and Indian communities alongside many Chinese. Two years later Huang, with an army numbering 600,000, captured Chang-an putting a formal end to the Tang Dynasty. Chang-An would decline from the world’s largest city into a small town[14].

[1] Mark Edward Lewis. China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty

[2] This is only the central government in Chang-an- far more officials worked in provincial and local government in the Tang Dynasty. Norman P. Ho, A Look into Traditional Chinese Administrative Law and Bureaucracy: Feeding the Emperor in Tang Dynasty China, 15 U. Pa. Asian L. Rev. 125 (2019).

Available at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/alr/vol15/iss1/10

[3] Mark Edward Lewis. China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty

[4] Mark Edward Lewis. China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty CH. 9

[5] Mark Edward Lewis. China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty CH 9

[6] Montgomery, Lazlo. "China History Podcast- 096 - Wang Xizhi." SoundCloud. Accessed May 30, 2022.

[7] Mark Edward Lewis. China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty

[8] Oftentimes in surface-level overviews of Chinese history or on the internet this figure is used to justify the statement that 35 million people died in the An-Lushan rebellion. To my surprise, this number has even been mentioned in academic journals.

[9] Mark Edward Lewis. China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty

[10] Mark Edward Lewis. China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty

[11] Mark Edward Lewis. China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty

[12] Kuhn, Dieter. The Age of Confucian Rule: The Song Transformation of China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011.

[13] Kuhn, Dieter. The Age of Confucian Rule: The Song Transformation of China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011.

[14] Luoyang would remain a major urban center